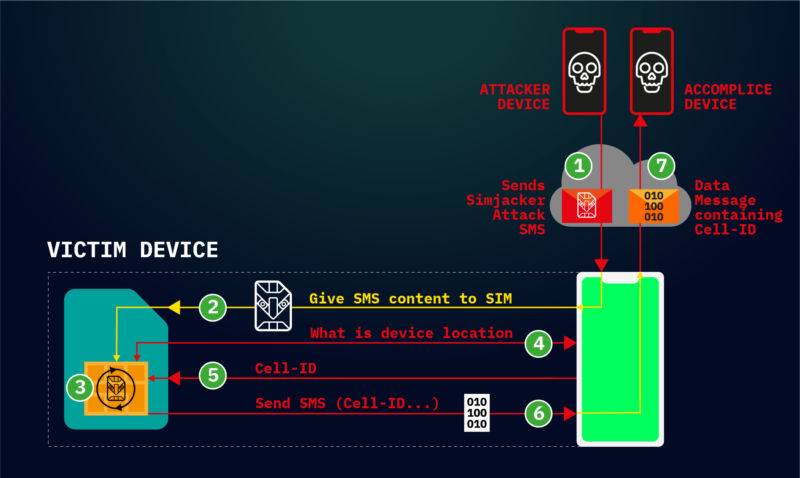

Attacks work by sending commands directly to applications stored on SIM cards.

Hackers are actively exploiting a critical weakness found in most mobile phones to surreptitiously track the location of users and possibly carry out other nefarious actions, researchers warned on Thursday.

The so-called Simjacker exploits work across a wide range of mobile devices, regardless of the hardware or software they rely on, researchers with telecom security firm AdaptiveMobile Security said in a post. The attacks work by exploiting an interface intended to be used solely by cell carriers so they can communicate directly with the SIM cards inside subscribers’ phones. The carriers can use the interface to provide specialized services such as using the data stored on the SIM to provide account balances.

Simjacker abuses the interface by sending commands that track the location and obtain the IMEI identification code of phones. They might also cause phones to make calls, send text messages, or perform a range of other commands.

“Pretty f***ing bad”

Dan Guido, a mobile security expert and the CEO of security firm Trail of Bits, told Ars the threat looked “pretty fucking bad.” He added: “This attack is platform-agnostic, affects nearly every phone, and there is little anyone except your cell carrier can do about it.”

Over the past two years, AdaptiveMobile Security researchers said, they have observed devices from “nearly every manufacturer being successfully targeted to retrieve location.” Device makers include Apple, ZTE, Motorola, Samsung, Google, Huawei, and even those who produce Internet-of-things products that contain SIM cards. While basic attacks work on virtually all devices, more advanced variations—such as making a call—would work only on specific phones that don’t require users to confirm they want the call to go through.

The attacks were “developed by a specific private company that works with governments to monitor individuals,” Thursday’s report said. The researchers didn’t identify the exploit developer but said it had “extensive access” to core networks using both the SS7 and Diameter traffic-routing protocols. In some cases, the attacker exploits widely known weaknesses in SS7 as a fall-back mechanism when Simjacker attacks don’t work.According to Motherboard reporter Joseph Cox, Sprint and T-Mobile said their customers weren’t vulnerable, and AT&T said its US-based network wasn’t affected. Verizon, meanwhile, said it had no indication it was affected either.

The attacks are happening to phones in “several” unnamed countries. Thursday’s report went on to say:

In one country we are seeing roughly 100-150 specific individual phone numbers being targeted per day via Simjacker attacks, although we have witnessed bursts of up to 300 phone numbers attempting to be tracked in a day, the distribution of tracking attempts varies. A few phone numbers, presumably high-value, were attempted to be tracked several hundred times over a 7-day period, but most had much smaller volumes. A similar pattern was seen looking at per-day activity, many phone numbers were targeted repeatedly over several days, weeks, or months at a time, while others were targeted as a once-off attack. These patterns and the number of tracking indicates it is not a mass surveillance operation, but one designed to track a large number of individuals for a variety of purposes, with targets and priorities shifting over time. The “first use” of the Simjacker method makes sense from this viewpoint, as doing this kind of large volume tracking using SS7 or Diameter methods can potentially expose these sources to detection, so it makes more sense to preserve those methods for escalations or when difficulties are encountered.

The attacks work by sending targeted phones an SMS message that contains special formatting and commands that get passed directly to the universal integrated circuit card, which is the computerized smart card that makes modern SIMs work. The message contains commands for software—called the S@T browser—that runs on the SIM card. The commands cause the S@T browser to send the location of the unique IMEI of the device in a separate SMS message to a number designated by the attacker.

Here’s how Thursday’s report explained it:

The attack relies both on these specific SMS messages being allowed, and the S@T Browser software being present on the UICC in the targeted phone. Specific SMS messages targeting UICC cards have been demonstrated before on how they could be exploited for malicious purposes. The Simjacker attack takes a different approach, and greatly simplifies and expands the attack by relying on the S@T Browser software as an execution environment. The S@T (pronounced sat) Browser—or SIMalliance Toolbox Browser to give it its full name—is an application specified by the SIMalliance, and can be installed on a variety of UICC (SIM cards), including eSIMs. This S@T Browser software is not well known, is quite old, and its initial purpose was to enable services such as getting your account balance through the SIM card. Globally, its function has been mostly superseded by other technologies, and its specification has not been updated since 2009, however, like many legacy technologies it is still been used while remaining in the background. In this case we have observed the S@T protocol being used by mobile operators in at least 30 countries whose cumulative population adds up to over a billion people, so a sizable amount of people are potentially affected. It is also highly likely that additional countries have mobile operators that continue to use the technology on specific SIM cards.

This attack is also unique, in that the Simjacker Attack Message could logically be classified as carrying a complete malware payload, specifically spyware. This is because it contains a list of instructions that the SIM card is to execute. As software is essentially a list of instructions, and malware is “bad” software, then this could make the Simjacker exploit the first real-life case of malware (specifically spyware) sent within a SMS. Previous malware sent by SMS—such as the incidents we profiled here—have involved sending links to malware, not the malware itself within a complete message.

The researchers said other commands UICCs are capable of executing include:

- PLAY TONE

- SEND SHORT MESSAGE

- SET UP CALL

- SEND USSD

- SEND SS

- PROVIDE LOCAL INFORMATION (including location, battery, network, and language)

- POWER OFF CARD

- RUN AT COMMAND

- SEND DTMF COMMAND

- LAUNCH BROWSER

- OPEN CHANNEL (CS BEARER, DATA SERVICE BEARER, LOCAL BEARER, UICC SERVER MODE, etc.)

- SEND DATA

- GET SERVICE INFORMATION

- SUBMIT MULTIMEDIA MESSAGE

- GEOGRAPHICAL LOCATION REQUEST

The attack reported Thursday is similar to one demonstrated in 2013 at the Black Hat security conference in Las Vegas.

“We could trigger the attack only on SIM cards with weak or non-existent signature algorithms, which happened to be many SIM cards at the time,” Karsten Nohl, the chief scientist at SRLabs who presented the 2013 findings, told Ars. “AdaptiveMobile seems to have found a way in which the same attack works even if signatures are properly checked, which is a big step forward in attack research.”

Nohl added that he doubted Simjacker was being widely exploited, since location data is generally not interesting to criminals and other methods exist to track specific targets. Those methods include SS7 attacks, phone malware, or simply buying the data from mobile networks or app makers who collect it.

In response to the attacks, the SIMalliance—an industry group representing major UUIC makers—issued a new set of security guidelines for cellular carriers. The recommendations include:

- Implementing filtering at the network level to intercept and block “illegitimate binary SMS messages” and

- Making changes to the security settings of SIM cards issued to subscribers.

As Nohl noted, snoops have long had a variety of ways to track the location of many cellular devices. Thursday’s report means that, until carriers implement the SIMalliance recommendations, hackers have another stealthy technique that previously went overlooked.

Stay connected